The Hidden Curves Of Urgency

Prioritize like a pro by understanding the relative urgency of a task over time.

Prioritization is never easy but over centuries of business we've developed tools to help us do it. We rely on tools like RICE and the Kano model to help us reason about the tradeoffs we make when we choose to do one thing over another.

One of the biggest reasons we need these tools is to stop our instinctive sense of urgency forcing us into an endlessly reactive mode. In such a mode, the primitive parts of our brains take over and use threat-sensitivity to work out what to do next. Our inner monologue sounds like this...

"What's about to catch fire? Let's focus on that. Oh wait ... a different thing is already on fire? Everything else can just wait."

Or, to quote the legendary US Marine, Lewis B "Chesty" Puller...

"We're surrounded. That simplifies the problem."

Pushing Back On Urgency

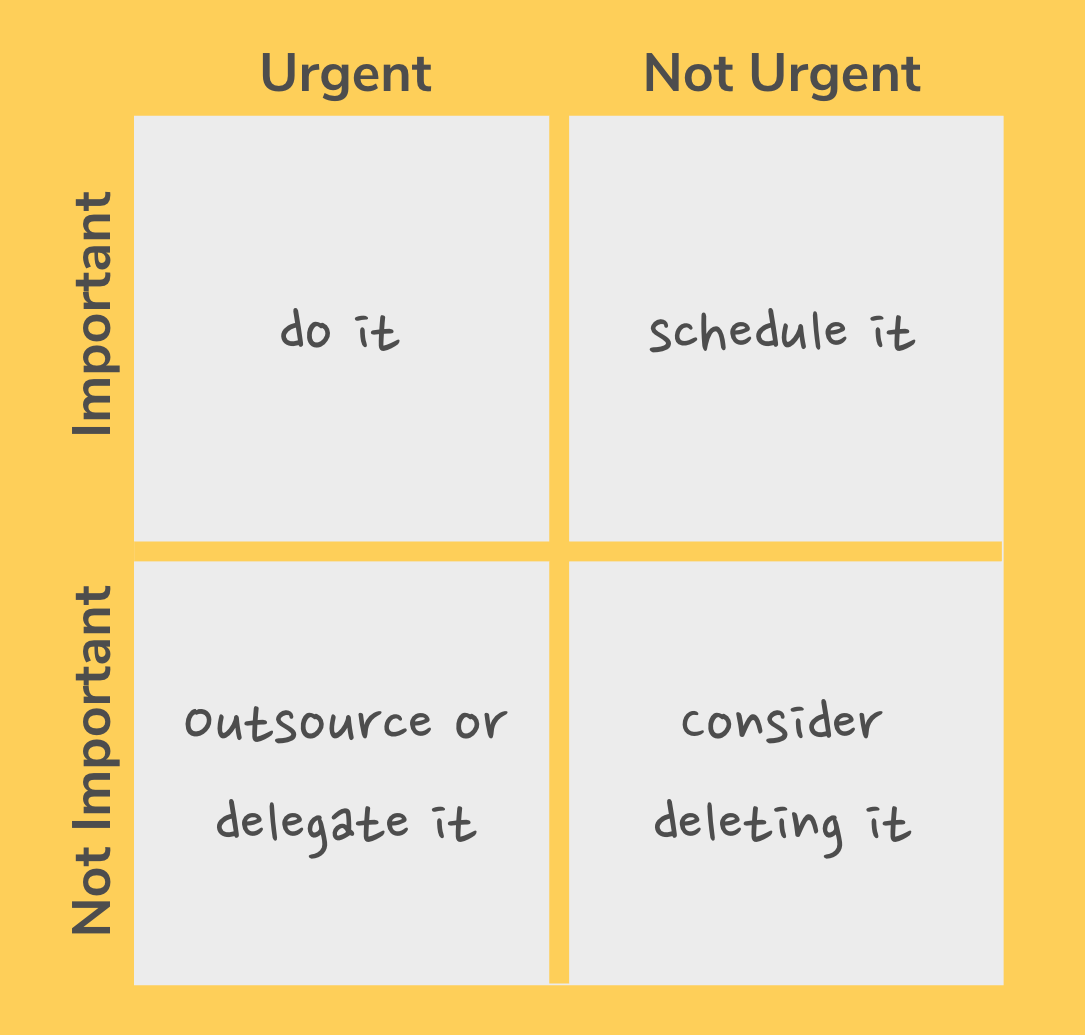

One familiar tool to help with such urgency-bias is the Eisenhower prioritization matrix. It's the model where we ask tasks to fight with each other based on their relative urgency and importance...

We love using this tool because it is a powerful reminder of a simple truth: urgent things may have to be done but important things need to be done. In fact, ideally, we should strive to build our lives (professional and otherwise) on the basis of doing the things we consider important, not merely urgent.

Going Deeper

While the Eisenhower matrix is a great place to start, it doesn't offer a lot of detail about how to assess the relative urgency of a task.

Naturally, if a presentation is due tomorrow but a report is due next week, the presentation is more urgent than the report. That's uncontroversial but it hides two important, complicating factors...

- The urgency of a task can (and usually does) vary over time

- The variation over time is different for every task

Example

Consider preventative maintenance on a database system (clearing disk space, etc...). Such maintenance work costs an engineer some time but it is intended to prevent potential outages (which are far more costly than the maintenance).

In this example, imagine the engineer has just done her monthly maintenance work and the database is in good shape. Over the course of the month, disks start to fill up at a fairly predictable rate. As we approach the end of the month, the amount of free space is getting down to the point where an unusual amount of load could tip the database over into failure. Up until this point, the risk of doing nothing has been rising linearly but now that risk starts to accelerate.

In other words, the task's urgency had been rising in a linear fashion but, now, it's rising faster and faster. It's the exact same task but the rate of change of its urgency has changed due to environmental factors.

Defining Urgency

This thought experiment involving database maintenance allows us to think more generally about exactly what we mean by urgency.

Put bluntly, why do we care if we do something now, tomorrow, next week or next year?

It can only be that the task in question is time-sensitive. In other words, negative consequences will occur if we don't get it done in a certain amount of time. Maybe a database server will malfunction. Maybe we won't get that lucrative contract. Maybe we'll lose someone's trust.

Therefore, the relative urgency of two tasks is nothing more than the relative sizes of the negative consequences of failing to do them in time.

That's why we use the following definition...

Urgency is the impact of failing to do something now

It's All About The Curves

This brings us back to the idea that urgency isn't automatically a linear thing - i.e it doesn't necessarily grow steadily over time. The universe just isn't that simple 😝.

Instead, we can think about different growth modes. Then, when we attempt to weigh the relative urgency of two tasks, we can ask a more sophisticated pair of questions...

- What is the relative urgency of tasks A and B?

- How will that relative urgency change over time as they both go through their unique growth modes?

The second of these two questions allows us to think about the fact that, while A may be more important than B today, things might be reversed a week from now.

We've seen some very common growth modes when helping people think about relative urgency...

Flat Progression

The consequences of not doing this thing will be the same a week, a month, or even a year from now.

For example, let's say that I want to learn how web APIs work. I don't need this information for my work, I'm just really curious. If, a year from now, I still haven't learned about them then the only consequence will be that I might be a little irritated that I never did so.

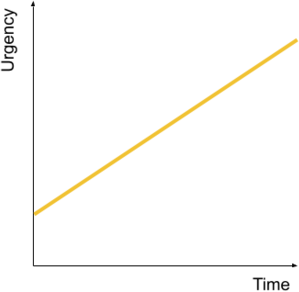

Linear Progression

The negative impact of not doing this thing grows steadily over time.

For example, imagine that the IT equipment costs in my company are proportional to the number of people who work here. Then suppose that we know the staff size is going to grow linearly over the next year. If I keep deferring the project to change how we buy that equipment, our costs will get predictably more expensive month-over-month.

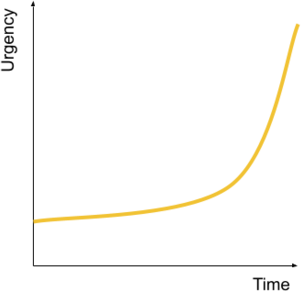

Exponential Progression

The problems that arise from not doing this thing grow at a faster and faster rate. It's a runaway effect. If it isn't caught in an early part of the curve, it'll quickly become severe enough that there's no choice but to consider it priority-one.

For example, picture a deteriorating dam. The risk that it will fail grows slowly at first but, beyond a certain point, the rate of deterioration becomes proportional to the amount of deterioration and the risk of collapse accelerates catastrophically.

Fun fact: the word catastrophe is from the greek meaning to (down)turn suddenly.

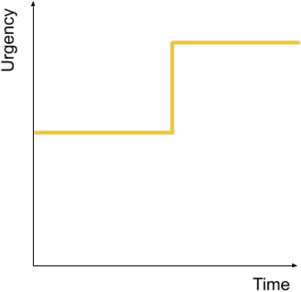

Step Change Progression

The negative impact of failing to act here is basically constant until a particular date is reached. Then it goes up suddenly to a new level.

For example, consider a regulatory issue where your company has to be in compliance by a certain date. Imagine that, after the deadline, your company will be fined every day until you are compliant. In this case, the urgency (the negative consequence of not acting) goes up suddenly when the deadline is reached.

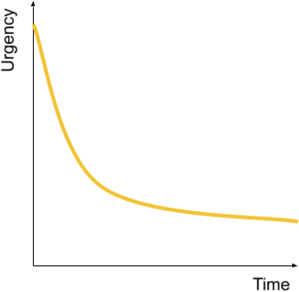

Decaying Progression

Finally, there are the issues that get less urgent over time. Often such issues are associated with a window of opportunity that has passed. During that window, the benefits of acting quickly were at their peak but, now, those benefits are tailing off.

The most obvious example of this kind of situation would be the first mover advantage wherein you want to bring a product to market before your competitors. Once that opportunity has passed, the benefits to be gained with a speedy release start to decline. So the release becomes less urgent.

As an aside, this is actually a good example of a situation where urgency can be a terrible basis for prioritization. Once you find yourself in the second mover position, it's critical to use importance to drive your decision making as urgency is now a misleading motivator.

Putting This Into Practice

So what now?

This more nuanced model around how urgency behaves allows us to revisit how we think about building (for example) an Eisenhower matrix. It gives us a nudge to think about the spread of relative urgencies between tasks and how that spread might change over time.

Briefly, the process goes like this...

- List the 5-10 tasks / items that you want to rank by urgency.

- Choose the growth mode listed above best fits each one.

- Attempt an initial ranking that reflects their relative urgency right now. If they all have the same growth mode, you're done - the rest of the process won't be useful.

- Now cycle forward in your head to next week and try the ranking again assuming that none of them got done in that time.

- Then do the same thing for next month.

- Then do it one last time for next quarter.

With those steps done, you will see the evolution of the urgency ranking over time. This will allow you to think about which ranking best takes account of the ultimate urgency of the tasks and balances that with how much you can get done in the next week, month and quarter.

If you'd like a worksheet to help you run through this process, we have one available as part of our tools bundle.

Once you get comfortable using the process, remember that (to use the Eisenhower model) prioritization comes from a blend of importance and urgency. As such, the urgency rankings you generate will still only be part of the story when it comes to deciding what you should prioritize.

As ever, if you learn something interesting while applying these tools, we'd love to hear from you.

You might be interested in our Decision Making workshop, designed to help teams make better-aligned, better-informed decisions whilst avoiding analysis paralysis.

We also provide leadership coaching to help you tackle challenges and grow.